Exploring the Friendship Paradox: Why Your Friends Have More Friends

Written on

Understanding the Friendship Paradox

The friendship paradox is a notable social phenomenon where individuals typically have fewer friends than their friends do, on average. This idea can be misinterpreted when viewed through popular articles. Let's delve deeper into this intriguing concept!

Initially, it may seem challenging to quantify this paradox, which might explain why it wasn't highlighted until 1991. In Scott Feld's foundational work, "Why Your Friends Have More Friends Than You Do," he proposed that this realization could lead to feelings of inadequacy. In the pre-digital era, tracking the number of friends friends had was cumbersome. However, with platforms like Facebook, it's now easier than ever to analyze such data.

For instance, let's examine my own Facebook connections. I have 374 friends, a number that raises questions. To gain insights, I randomly selected ten friends and recorded how many friends they each have:

- Friend 1: 522

- Friend 2: 451

- Friend 3: 735

- Friend 4: 397

- Friend 5: 2074

- Friend 6: 534

- Friend 7: 3607

- Friend 8: 237

- Friend 9: 1171

- Friend 10: 690

Calculating the average, these friends collectively boast 1042 friends, indicating that I have fewer friends than they do, on average. Interestingly, I only surpass one of them in friend count—poor Friend 8.

However, this isn’t a paradox if you know my social circle. Let's shift our focus to Friend 2. With 451 friends, we can explore Friend 2's connections. By checking the profiles of Friend 2's friends, we find the following counts: 790, 928, 383, 73, 827, 1633, 202, 457, 860, and 121. Here, the average number of friends among Friend 2’s connections is 627, which exceeds their own count of 451. This pattern likely persists if we examine all my friends—most will have fewer friends than their friends do, despite many having more friends than I do!

The intuitive sense of paradox arises when we consider a comparison to height. For example, if you are shorter than average, you might assume that at least half of the population is taller than average. However, this logic doesn't seamlessly apply to friendships. The discrepancy lies in the distribution of friends; there are numerous individuals with few friends, while only a handful possess many.

In social networks, popular individuals are often included in many friend circles, while those with fewer connections tend to remain less visible. In my case, I have a relatively low friend count, leading to the appearance that others have more friends than I do. Yet, those with a larger social circle likely won’t count me among their friends. This is evident in the fact that Friend 2 and I share only two mutual friends.

Examining Networks: Zachary's Karate Club

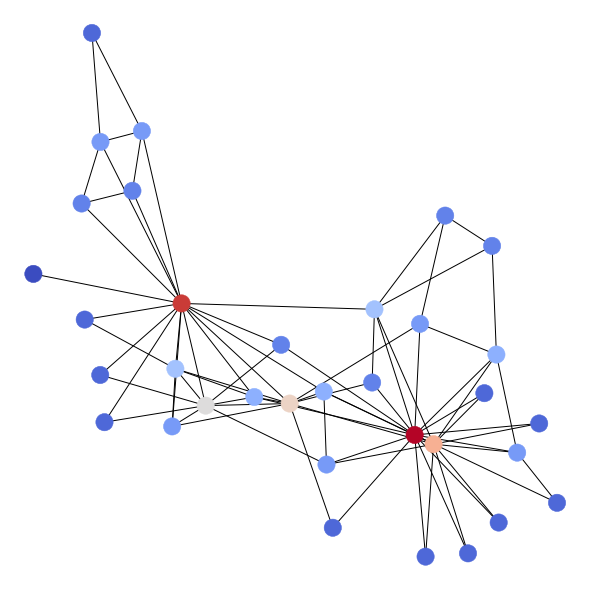

To understand this phenomenon better, let's analyze smaller networks, such as Zachary's karate club from the 1970s.

This network comprises 34 members and illustrates their interactions outside of class. Nodes are color-coded based on the number of friends each individual has. For example, one member has only one friend, while another boasts 17 friends.

Computational analysis reveals that in Zachary's karate club:

- Approximately 85.29% of members have fewer friends than their friends do on average.

- About 70.59% have fewer friends than most of their friends.

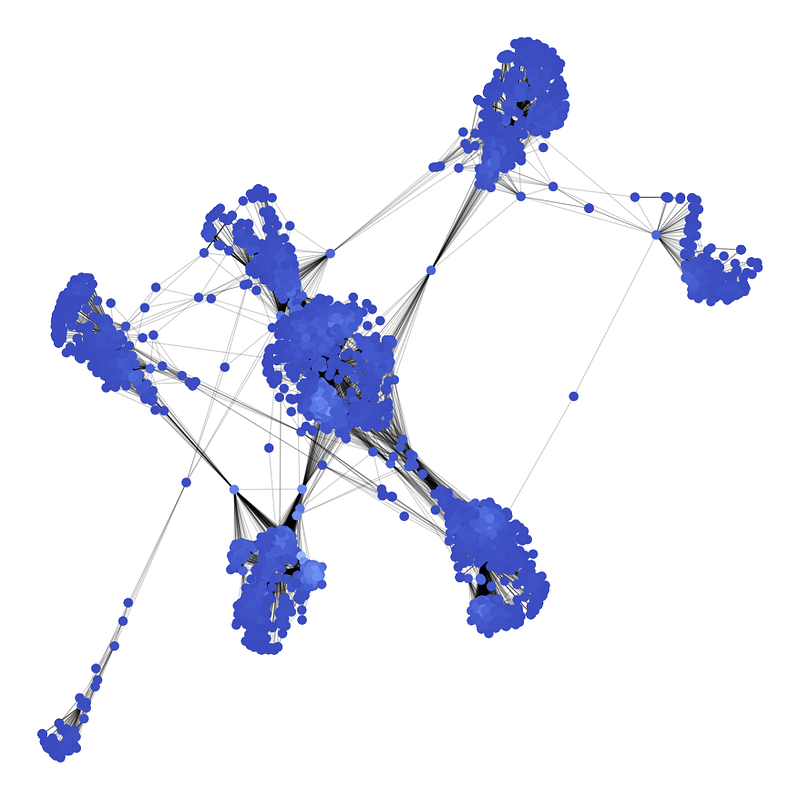

Next, let's visualize this phenomenon on Facebook.

This Facebook Ego Graph demonstrates community structures and clustering around popular individuals. Analyzing data from ten anonymized users reveals:

- 87.47% of individuals have fewer friends than their friends do on average.

- 71.92% have fewer than most of their friends.

These figures are remarkably similar to those observed in Zachary's karate club, suggesting a consistent trend in social networks.

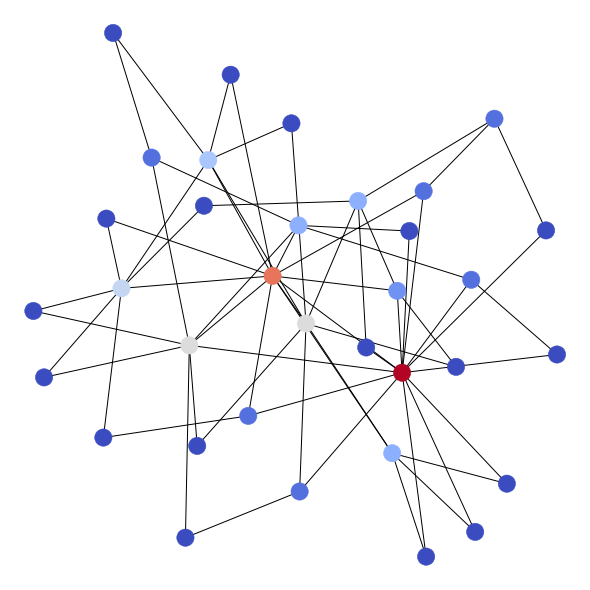

Simulation: Testing the Friendship Paradox

To further validate these findings, simulations can be employed. In this case, we utilize the Barabási–Albert model, which mimics social network formation by connecting new nodes to existing ones, favoring well-connected nodes.

We can simulate a network of 34 individuals and analyze the resulting connections.

The numerical data obtained from this simulation reveal:

- 79.41% of individuals have fewer friends than their friends do on average.

- 70.59% have fewer than most of their friends.

To enhance confidence in our conclusion, we repeat the simulation across 10,000 random social networks, leading to the discovery that:

- 79.31% have fewer friends than their friends do on average.

- 65.31% have fewer friends than most of their friends.

As the size of the network increases, the proportion of individuals with fewer friends than their friends also tends to rise.

Exploring Broader Implications

Interestingly, the friendship paradox extends beyond social connections. Individuals often feel they have fewer resources, followers, or happiness compared to their peers. This realization can be disheartening, but there's a silver lining: since friends often have more connections, they may also experience the spread of illnesses or trends sooner.

Research indicates that tracking friends instead of randomly chosen individuals can lead to more efficient disease monitoring, as friends tend to get sick before their connections.

Ultimately, the friendship paradox holds true in most social networks. The average condition will always demonstrate that individuals have fewer friends than their friends do. However, the majority condition may not apply universally, as networks lacking highly popular individuals can exhibit different dynamics.

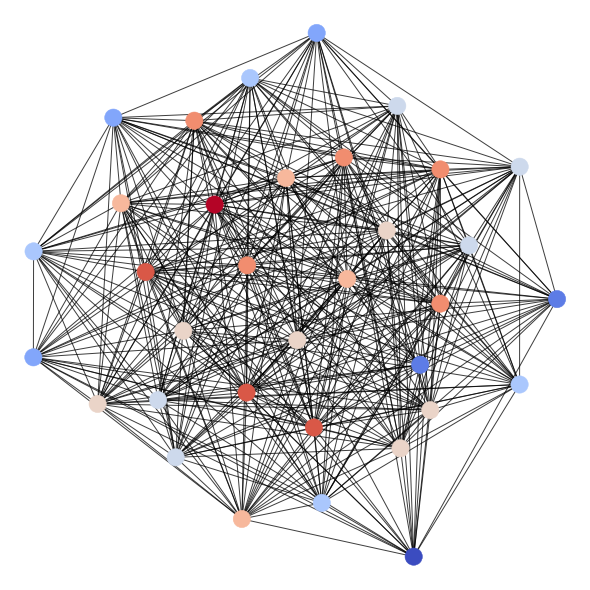

Consider an alternative social network built on the Erdős–Rényi model, where each person has a fixed probability of being friends with others.

In this scenario, both metrics yield 44.12%—indicating a balanced distribution of friendships.

Conclusion

It's clear that if everyone had the same number of friends, they would also have the same number of friends as their friends. This concept applies even in more evenly distributed networks. Such findings may support the idea of egalitarian communities, but hierarchical structures often emerge to manage complex connections.

For now, let's keep this intriguing exploration to ourselves. Instead, encourage a friend to share the insights!

(All simulations and data for this article are available on GitHub below.)

The first video title is "Why Your Friends Have More Friends than You" - YouTube. This video delves into the reasons behind the friendship paradox and explores how our connections affect our social interactions.

The second video title is "The Math That Proves Your Friends are More Popular Than You" - YouTube. This video breaks down the mathematical principles that underpin the friendship paradox, providing a clearer understanding of this social phenomenon.