Exploring Lovecraft's Cosmic Horror in Light of Modern Cosmology

Written on

Note: the author’s cosmic horror novel The Shadow Over Sarnath has just been published.

I. Introduction: Lovecraft, Cosmic Horror, and the Contemporary Perspective

What do we mean by cosmic horror? This concept does not originate from traditional sources like eerie noises or sudden frights, but rather from a profound awareness of our position in the universe—an awareness that aligns surprisingly well with modern scientific understanding.

Cosmic horror implies that truly confronting this awareness could lead to madness, whether swiftly or gradually.

Is this a stretch?

Allow the renowned writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890–1937) to elaborate. In the opening of one of his best-known tales, he states:

> “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but someday the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.” (The Call of Cthulhu, 1928).

This excerpt reveals key traits of cosmic horror. Our perceptions and logic are alarmingly limited. The familiar provides comfort, while the unknown often evokes discomfort. A sudden encounter with the entirely alien can be utterly frightening.

Could it be that this sense of familiarity is a mere illusion, a protective cocoon on our “placid island of ignorance”? Lovecraft also mused about the:

> “fear and awe we feel when confronted by phenomena beyond our comprehension, whose scope extends beyond the narrow field of human affairs and boasts of cosmic significance.”

He further described how this form of horror:

> “suspends our morality, desires, and interests, nullifying our expectations of how the world works and leading to a profound existential dread.”

This dread arises from our:

> “contemplation of mankind’s place in the vast, comfortless universe revealed by modern science.”

Such insights present a starkly different view of our existence in the cosmos, fundamentally challenging our cherished beliefs, particularly our sense of moral significance. We tend to act as if we are the epicenter of existence.

However, the sciences present a contrasting narrative.

They inform us that we are merely one of countless species, a product of random Darwinian evolution, residing on a small blue planet in an inconsequential corner of a vast galaxy, which is one of billions.

Our existence is a result of chance, with no grand cosmic forces orchestrating our fate.

The contemporary worldview stemming from these insights suggests there are no ultimate reasons for our existence, nor for our moral choices. This realization led existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) to conclude that it is entirely up to us to determine our own essence.

Both Lovecraft and Sartre recognized the trajectory of modern thought. Nietzsche’s Zarathustra declared in the 1880s that God was dead, a casualty of Science. Yet, even from a humanist perspective, the aftermath of God’s demise was not encouraging.

Lovecraft's life was marked by hardship. He was not “at home in the world.”

His father was institutionalized when he was just two years old and passed away six years later. An only child, Lovecraft was overprotected by his mother, Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft. For a time, they lived with his affluent maternal grandparents in Providence, Rhode Island.

Tragedy struck again when his grandmother died when he was six, casting a shadow over their household. Distressed by the mourning attire worn by his mother and aunts, he began dreaming of dark-winged creatures he termed night gaunts, which would abduct him from his bed and carry him over bleak landscapes. Such demonic figures emerged in his early stories, including “Dagon,” “The Outsider,” and “The Doom That Came to Sarnath.”

Gifted intellectually, Lovecraft delved into his grandfather’s extensive library, rich in scientific and historical texts, and was introduced to authors like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe, which ignited his passion for writing.

However, Lovecraft’s life took another turn when his grandfather passed away in 1904. Financial constraints forced him and his mother to relocate to a modest duplex, and he attended public school during his teenage years. There are indications he faced bullying, and even his mother labeled him “ugly.” At times, he would shield his face with a long coat when outdoors, likely contributing to the misanthropy he later exhibited. In 1908, he experienced what he termed a “nervous collapse.” Despite his desire to attend Brown University, he never completed high school. Instead, he turned to amateur scientific journalism, gaining local recognition.

Remarkably, he eventually found a partner in Sonia Greene, but their marriage was fraught with challenges. The move to New York City, where she worked, was particularly difficult for Lovecraft, who harbored a deep disdain for the city. He faced accusations of racism, which reflected common sentiments of the time regarding urban diversity.

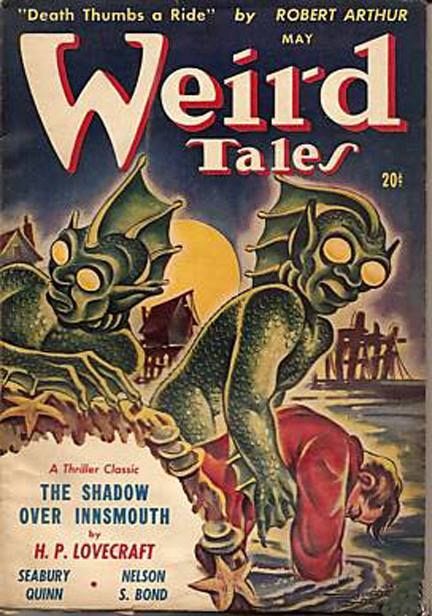

Ultimately, he returned to Providence, and their divorce was amicable. He lived in near poverty, using this period to compose longer works such as “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and others, earning minimal pay from pulp magazines like Weird Tales.

While Lovecraft’s readership was limited, those who discovered his work recognized its originality. He was a prolific correspondent, engaging with fans and fellow writers, who contributed to the unique “mythos” his narratives developed.

However, he remained largely invisible in the broader literary landscape and passed away at the young age of 47, feeling like a failure. His extensive letter-writing, numbering in the thousands, could not shield him from the isolation that plagued him.

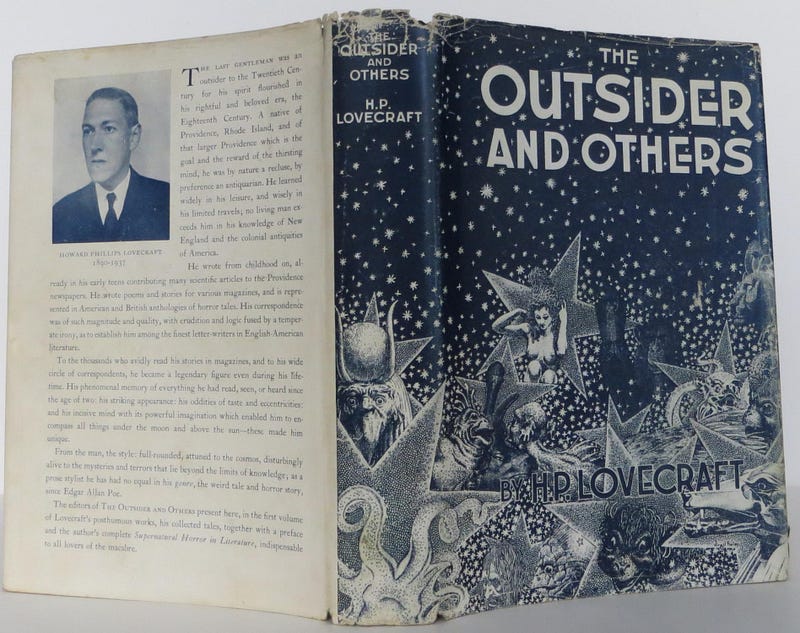

Among his correspondents was August Derleth (1909–1971), who founded Arkham House, a publishing house named after the eerie Massachusetts town Lovecraft created in his fiction. Arkham, home to Miskatonic University, featured prominently in Lovecraft's works. Derleth published The Outsider and Others (1939), which garnered critical acclaim.

Derleth’s efforts paved the way for both established and new writers in the emerging cosmic horror genre, including figures like Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard.

Lovecraft, unaware, would come to be regarded as one of the most significant writers of dark fiction, his name joining the ranks of literary giants like Hawthorne and Poe.

II. Cosmic Horror: A Closer Examination

A distinct worldview, complete with its pantheon, has emerged within the cosmic horror genre. Derleth coined the term Cthulhu Mythos, named after one of Lovecraft’s most iconic entities.

In essence, this worldview posits that prior to humanity's existence, Earth was colonized by ancient races from distant star systems—echoing the Silurian Hypothesis. These beings constructed colossal cities in places like Antarctica and remote Pacific islands. Some waged wars, while others practiced dark magic and were subsequently imprisoned by even more powerful entities Lovecraft referred to as Elder Gods, confined to hidden locations like the submerged city of R’lyeh, home to Cthulhu. Lovecraft’s creations often bore names reminiscent of ancient Hebrew or Egyptian origins, evoking both antiquity and malice.

These otherworldly beings remain, in a sense, imprisoned, yet their formidable minds can influence humans through dreams, awaiting the moment when “the stars align” to reclaim Earth. Occasionally, careless explorers unwittingly alert these beings to their presence, leading to chaos.

Encounters with and rituals to summon these entities are chronicled in ancient texts like the Necronomicon, attributed to the “mad Arab” Abdul Alhazred of the 8th century A.D. Lovecraft crafted an elaborate backstory for this book, claiming only five copies exist, one secured in the rare-books section of Miskatonic University.

These texts hint at:

> “the awesome grandeur of the cosmic cycle wherein our world and human race form transient incidents. They have hinted at strange survivals in terms which would freeze the blood if not masked by a bland optimism. But it is not from them that there came the single glimpse of forbidden eons which chills me when I think of it and maddens me when I dream of it. That glimpse, like all dread glimpses of truth, flashed out from an accidental piercing together of separated things…” (Call of Cthulhu).

So, what exactly is cosmic horror?

First, it invokes a vast cosmos in which humanity possesses no significance, obliterating our beliefs about our importance.

Second, we become mere playthings of ancient entities whose comprehension is beyond us, akin to how we perceive ants on a sidewalk—stepping on them without moral consideration.

Third, the horror stems from the fact that these beings do not embody “evil” in any meaningful sense; their actions are simply natural to them, akin to hunting for food or reproduction.

This concept manifests in the Alien franchise, where the android Ash describes the xenomorphs as:

> “the perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility… A survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

In my view, this moment encapsulates the film's most terrifying essence.

Alien adeptly merges hard science fiction with cosmic horror!

Attempts to seek out such creatures seem exceedingly ill-advised.

Some refer to cosmicism, a perspective that the universe itself is indifferent to our existence, contrasting with anthropomorphism, which either posits a deity or views the universe as a place where humanistic ethics can thrive, surviving Nietzsche’s nihilistic implications.

Humanists contend that the moral frameworks we've upheld for over 2,000 years can endure the universe depicted by modern science. Bertrand Russell's essay, “A Free Man’s Worship” (1903), reflects this hope.

Russell held optimism; Lovecraft did not. Who is correct? What does contemporary cosmology indicate?

III. The Journey to Current Cosmology: From Big Bang to Little Earth

Cosmology has advanced significantly since Russell's time. Even then, science appeared to undermine the notion of a benevolent deity who cares for us and ensures a favorable outcome.

Historically, thinkers like Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton displaced Earth from its supposed central position in Creation. The belief in a young Earth, calculated by Archbishop James Ussher to have originated in 4004 B.C., was challenged by fossil discoveries that suggested much older life forms and layered rock formations that could not be attributed to a singular catastrophic flood.

Sir Charles Lyell, often regarded as the father of modern geology, advocated for uniformitarianism, suggesting that “the present is the key to the past.” He warned against attributing the geological record to catastrophic events.

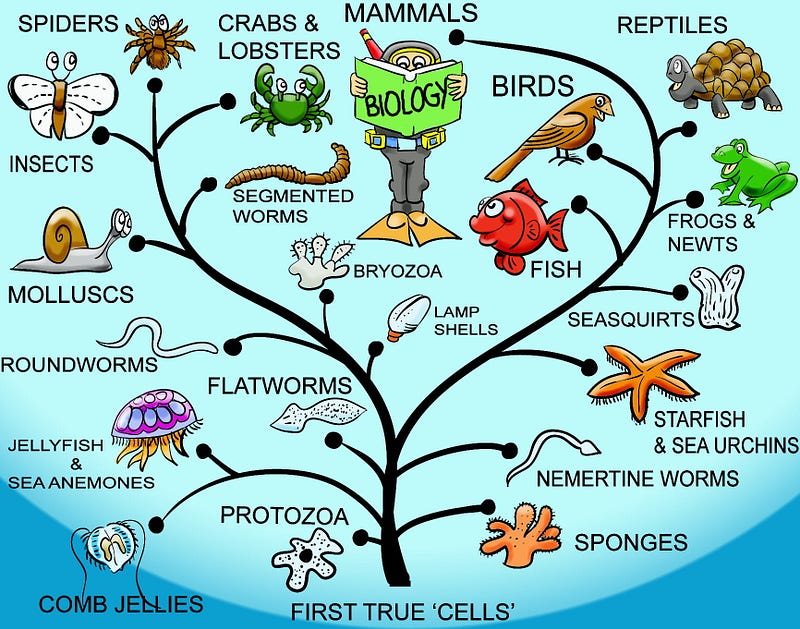

The most significant influence on comprehensive philosophical naturalism came from Charles Darwin, who introduced the concept of evolution by natural selection in On the Origin of Species (1859). This revolutionary idea reshaped biology and became a foundational principle in subsequent scientific thought, despite initial resistance from religious factions.

Today, it is widely accepted that Earth is approximately 4.54 billion years old, and the universe itself is about 13.79 billion years old. Recent studies suggest the universe could be even older—up to 26.7 billion years!

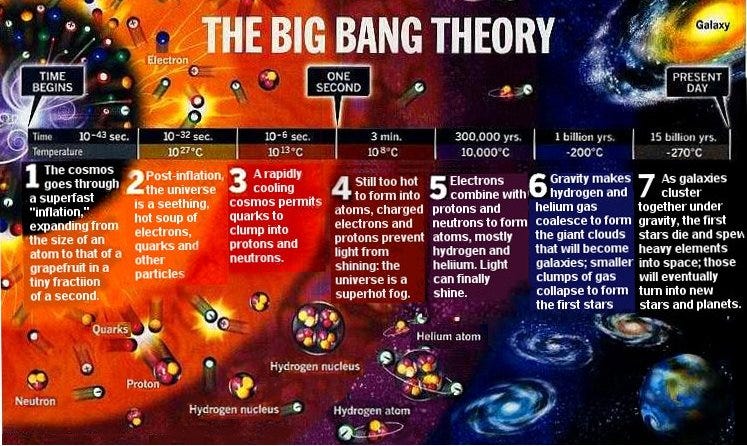

Regardless, it all began with a Big Bang!

Some interpretations indicate that this event initiated space and time. Since these are manifestations of a higher-dimensional phenomenon, it makes little sense to inquire about what preceded the Big Bang, just as it is nonsensical to ask what lies north of the North Pole.

It’s all a bit mind-boggling, no matter how you perceive it!

While many details remain elusive, it is believed that life on Earth originated through natural chemical processes, driven by intense electrical storms in an oxygen-free environment. Aquatic life eventually transitioned to land, with speciation continuing despite asteroid impacts that periodically disrupted evolutionary progress, such as the extinction event that ended the reign of dinosaurs. While geologic science has reintroduced a form of “light” catastrophism, the core principles remain unchanged. This process allegedly cleared the way for mammals to evolve, ultimately leading to humanity.

All of this unfolded on a remarkably small planet, our Little Earth!

These events transpired—unplanned, we are told!

This portrayal of existence is stark and devoid of divine presence. Far from “declaring God’s glory,” as the Psalmist claimed, the cosmos is dark and silent, occasionally violent, marked by events like asteroid impacts and supernova explosions.

Are we alone? Could there be other beings gazing into the cosmos, contemplating the same question?

If the assumptions of philosophical naturalism underpinning current cosmology hold true, why wouldn’t there be?

It’s crucial to note that we have no evidence supporting the existence of extraterrestrial life, let alone advanced civilizations. We have only organic molecules from a handful of meteorites—far removed from complex, self-replicating entities, or life as we understand it.

Thus arises the Fermi Paradox: “Where is everybody?”

In a universe that is theorized to be at least three times older than our planet, do we truly know what to search for?

Do we genuinely want to discover the answer?

Renowned physicist Stephen Hawking cautioned against the dangers of broadcasting signals into deep space. He was far from naive.

The absence of evidence for extraterrestrial life is not definitive proof against it. The idea is not without merit.

It is often stated that we are either alone in the universe or we are not, and both scenarios are unsettling!

I suspect that the pursuit of extraterrestrial life reflects a psychological urge: we, including modern scientists, do not wish to be alone in a godless universe!

This drive might explain why both professional and amateur astronomers have identified over 5,500 exoplanets. While most are inhospitable environments, a few appear Earth-like, situated in their star’s “Goldilocks zone.”

Some scientists have attempted to temper the notion that complex life forms like ourselves are common, even if microbial life could develop in oceans on other worlds. They argue that in the case of Earth, numerous factors came together just right: proximity to the sun, abundant water, a significant moon, gravitational effects, axial tilt for seasonal variation, plate tectonics, and a favorable balance of radiation from the host star, among others.

Extraterrestrial beings may be exceedingly rare, but they are not impossible.

This all ties back to the infamous Drake Equation, which attempts to quantify the probabilities.

Thus, a quiet What if? emerges. This What if? has served as fertile ground for science fiction and horror writers alike.

For roughly 80 years, we have been transmitting radio signals into space, creating a “sphere” of detectability that extends 160 light years. And then there’s Voyager…

What if something out there intercepted one of our civilizational signals and traced it back to our pale blue dot?

With such questions, the intrigue truly begins!

IV. Why a Lovecraftian Scenario Is Credible in Modern Science

In truth, we are navigating without a clear guide. We have one example of a life-sustaining planet—our own. At best, we possess hypotheses regarding the origins of life here. If any of these are plausible, similar processes could have unfolded elsewhere—perhaps billions of times, on planets of varying ages orbiting stars much older than our own.

The hypothetical process of life emerging from non-life through physical and chemical means is termed abiogenesis. This process may have yielded vastly different outcomes elsewhere—potentially even before Earth came into existence.

Let’s explore this notion.

Assuming for the sake of discussion that current cosmology is fundamentally accurate regarding the universe’s age, with only minor details to clarify, then there is ample time—eons, in fact—for intelligences to have emerged elsewhere, potentially building civilizations that, if they survived, could be billions of years older than us!

Considering the vast expanse of space, with quintillions of cubic light years and billions of galaxies, each containing hundreds of millions of stars, it would be cosmically (even absurdly!) strange if abiogenetic processes, as posited by philosophical naturalism, resulted in life occurring only once!

Why on Earth would that be the case?!?!?!

The Drake Equation attempts to quantify these possibilities.

But again, where is everybody?

The Fermi Paradox suggests the presence of a Great Filter that significantly reduces the number of sustainable civilizations. This Great Filter may represent a critical challenge or set of challenges that an advancing civilization encounters at a pivotal moment in its development. Failure to navigate past this Great Filter could result in its collapse and disappearance in this vast, indifferent cosmos.

Perhaps a civilization fails to find a sustainable energy source without compromising its ecosystem and endangering its own existence.

Or it creates an AI that turns against its creators. (This theme resonates with Harlan Ellison’s haunting short story “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” which received numerous accolades.)

Imagine that only a minuscule fraction—less than 0.001%—of civilizations successfully navigates its Great Filter. That’s a discouraging statistic!

Yet, given the hundreds of millions of stars in our galaxy alone, that still amounts to tens of thousands of civilizations potentially existing across different epochs…

If any of them are out there, could they reach us?

This remains a challenging question, as we lack clear visibility!

Assuming the speed of light is the ultimate limit in space-time, it would take a spacecraft traveling at light speed over four years to reach Proxima Centauri, our closest stellar neighbor.

We have no clear understanding of how to accelerate a spacecraft to such speeds or protect it during transit (even tiny particles invisible to the naked eye could become deadly projectiles at such velocities).

Could we, or someone else, somehow surpass the speed of light with a “warp drive” (as depicted in Star Trek), a “jump gate” (as seen in Babylon 5), or by “folding space” (as suggested in Dune)?

Such beings might, if they overcame their Great Filter and advanced scientifically and technologically for long enough, find ways to project their consciousness across space and time, despite how this might contradict principles of naturalism (we need not delve into that here). They could potentially usurp our bodies, reminiscent of Lovecraft’s themes of body-snatching!

One of Lovecraft’s most intriguing tales, “The Shadow Out of Time,” is based on this premise.

V. Lovecraftian Entities Are Not Supernatural

There’s no justification for viewing Lovecraftian beings as “supernatural.” Recall Arthur C. Clarke’s Law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Imagine Aristotle trying to comprehend a laptop… Now picture insects crawling around a device left on the floor. Would they even recognize it?

Previously, I used the term preternatural, which refers to something appearing to exist beyond or outside the natural realm. Emphasis on appearing.

Such entities, having successfully navigated their Great Filter and now millions of years ahead of us, might possess technologies so advanced that they have integrated them into the very fabric of the universe itself, into space-time itself.

Perhaps our understanding of space-time is a product of their design.

Intelligent Design, albeit significantly different, particularly if the Designer is not our familiar Christian God! (Who said an Intelligent Design theorist must be a Christian?)

We might even delve into the idea that we are within, or even a product of, another entity’s simulation—a concept explored by philosophers like Nick Bostrom from Oxford.

What kind of beings might create a simulation?

It becomes even more unsettling.

We would have no insight into their motivations.

We can speculate that if such entities successfully addressed their Great Filter challenges, they are likely benign—by some measure. They wouldn’t have reached their current state had they not overcome past tendencies toward malevolence or basic folly (such as greed, tribalism, and ecological destruction).

But consider: were you malevolent when you unintentionally stepped on those ants?

I suspect not. You barely even noticed them.

Perhaps they can hardly perceive us—unless we draw their attention.

And if they respond, we wouldn’t comprehend what we were witnessing.

Or if they decided it was time to “pull the plug”…

VI. Conclusion: Should You Fear What Might Be Out There? (Or Already Here?!)

Should any of this evoke fear? That ultimately depends on your perspective.

None of these ideas directly impact our daily lives: whether selling items, writing code, managing documents, serving tables, or composing articles on Medium.

Yet, a small part of me ponders the possibility of being struck suddenly by something unforeseen.

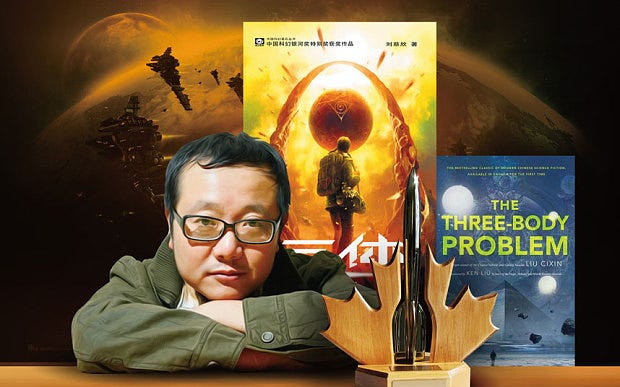

Consider a particularly unsettling passage from Cixin Liu’s remarkable science fiction novel The Three-Body Problem, in a chapter titled “The Shooter and the Farmer.”

Allow Mr. Liu to take the stage:

> “When the members of the Frontiers of Science discussed physics, they often used the abbreviation SF. They didn’t mean ‘science fiction,’ but the two words ‘shooter’ and ‘farmer.’ This was a reference to two hypotheses, both involving the fundamental nature of the laws of the universe.”

In the shooter hypothesis, a skilled marksman shoots at a target, creating holes every ten centimeters. Suppose the target is inhabited by intelligent, two-dimensional beings. After observing the universe, they conclude: “There exists a hole in the universe every ten centimeters.” They mistake the marksman’s random act for an immutable law.

The farmer hypothesis, however, leans toward horror. Each day on a turkey farm, the farmer arrives to feed the turkeys. A scientist turkey, having observed this routine for nearly a year, announces: “Every morning at eleven, food arrives.” Yet on Thanksgiving morning, food does not arrive; instead, the farmer comes and slaughters the entire flock (p. 74).

In Liu’s brilliant narrative, several renowned physicists have taken their own lives, having reached a deeply unsettling conclusion: the physical laws they believed to understand do not exist.

What should trouble the “scientific minds” who have read this far is that everything we’ve discussed here aligns with actual scientific discovery!

VII. Afterward: Why The Shadow Over Sarnath?

I’ve contributed my own novel-length addition to the cosmic horror subgenre, stepping into Lovecraft’s universe with a few variations. (This is actually my second such work; the first, a shorter piece, is here.) This isn’t intended to be a sales pitch. While it would be wonderful if you chose to purchase it, my motivations for writing it were more complex.

One reason is that I could. I enjoy a compelling, frightening narrative as much as anyone (you think?), and I’ve dedicated time to studying the mechanics behind these stories. Crafting relatable characters is an engaging challenge. I experience a thrill when a character emerges organically as I write, taking on actions and thoughts I hadn’t anticipated! (Character development was not one of Lovecraft’s strengths; his protagonists often resemble him: psychologically isolated intellectuals caught in terrifying circumstances.)

A deeper motivation for writing Shadow was my desire to explore the godless universe many writers (including those on Medium) depict. I aimed to connect this specifically to the implications of the cosmos' vast age, suggesting that we are neither alone nor the first.

Set in Lovecraft’s created world, Sarnath, alongside its “still lake fed by no stream,” the backstory provided by his tale “The Doom That Came to Sarnath,” and my introduction of Bokrug, along with new characters and a scenario that thrusts them into a horrifying clash with something that “broke a passage open” from its realm to ours, I had a plot!

Parts of Shadow seemed to write themselves!

What are my true feelings about all this? Are we condemned to a godless existence, or could God exist after all?

I’ll reserve that discussion for another time. My main point is that philosophical naturalism presents a bleak picture. It aligns seamlessly with the universe of cosmic horror, which thrives on the notion that entities far older than we are may exist, shaping what we perceive as the very fabric of reality—something they could manipulate at will.

As demonstrated in the Shooter and the Farmer, which suggests that what we label as physical law may be an illusion.

As with the concept that we might be existing within a simulation. What occurs if the entity that designed the simulation grows bored or decides to intervene?

That question might keep you awake tonight.

No, we probably won’t be zapped without warning. Not that we would recognize it if we were.

Here’s a suggestion: embrace the person you cherish the most. Tell them you love them.

Just in case.