Understanding the Catastrophic Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai Eruption

Written on

Chapter 1: The Eruption Unfolds

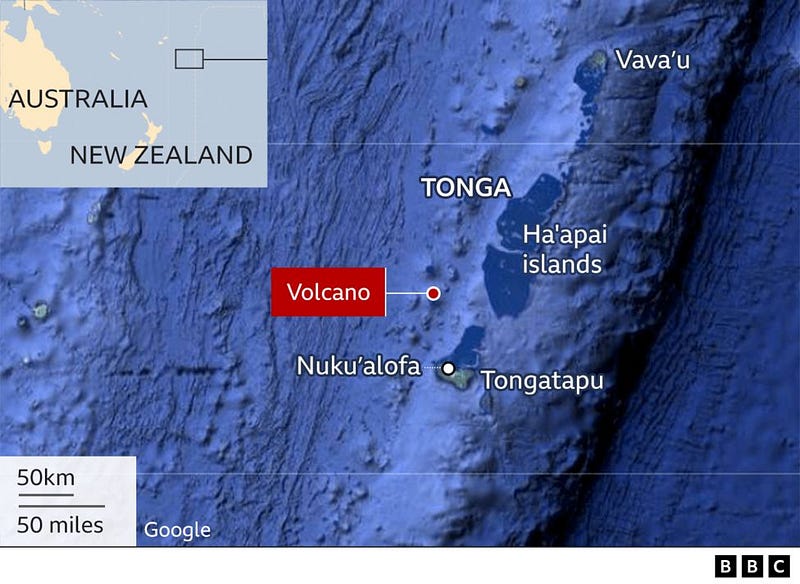

On January 15, a significant volcanic eruption occurred in the Kingdom of Tonga, leading to devastating tsunamis and disrupting communication networks.

This paragraph will result in an indented block of text, typically used for quoting other text.

Section 1.1: Background of the Eruption

In late December 2021, the underwater volcano Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai started to erupt. The initial activity went largely unnoticed on the global stage, with only local media coverage, as the situation seemed stable. Satellite images indicated the formation of an island due to the eruptions, but the activity subsided, and the volcano was deemed dormant by January 11, 2022.

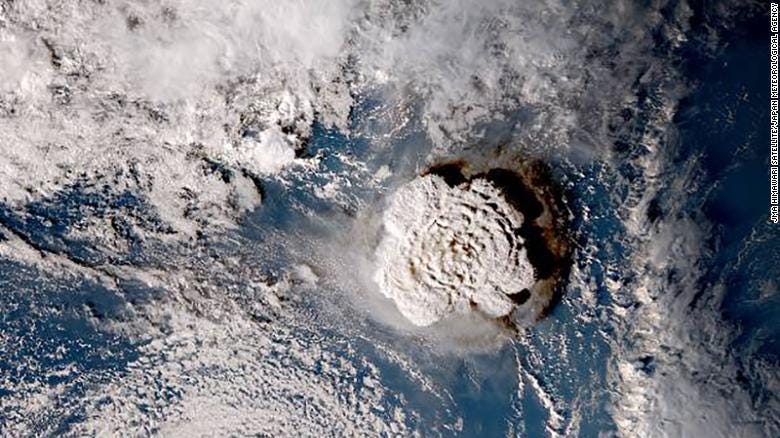

However, on January 14 at 0420 UTC (5:20 PM local time), a far more intense eruption occurred, launching a massive cloud of ash, steam, and gas into the atmosphere, reaching heights of nearly twenty kilometers. Subsequent analyses suggested that the plume may have soared as high as thirty kilometers. Observers from a nearby ship noted the base of the ash cloud measured approximately five kilometers wide.

Section 1.2: Widespread Impact

Reports from social media indicated that the explosion was audible as far away as Australia, Samoa, and Fiji, with some claims even reaching Anchorage, Alaska. The eruption caused significant ashfall across the islands of Tonga, prompting tsunami warnings for both the nation and the broader Pacific region. The initial tsunami wave measured around twenty centimeters, which escalated to nearly two meters in subsequent waves. Images released by the Tongan government indicated that several villages were completely destroyed, with extensive damage across multiple islands.

Additionally, the eruption severed an underwater communication cable, complicating rescue operations and hindering the government’s ability to evaluate the full extent of the damage. Airports were closed due to ash accumulation obscuring runway markings, limiting inter-island communication to patrol boats.

At least three fatalities were reported in Tonga, with many more injured and unaccounted for, but the tsunami warnings likely prevented further casualties. The tsunami waves also affected regions far beyond Tonga; Japan experienced waves measuring eighty centimeters, which damaged harbors and boats. North American coasts saw similar impacts, with Alaska recording waves between twenty and 100 centimeters, while California also reported increased wave activity.

One of the most intriguing aspects of this eruption was the significant electrical activity within the ash cloud, leading to hundreds of thousands of lightning strikes. The GLD360 lightning detection network reported over 200,000 discharges within just one hour of the eruption.

This video, How NASA Sees the Life Cycle of Volcanic Island Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, provides an insightful look into the eruption and its aftermath, showcasing the incredible power and impact of volcanic activity.

Chapter 2: Monitoring from Above

In the lead-up to the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruptions, a variety of satellites, including those from Planet Labs and the European Space Agency’s Sentinel constellation, were closely monitoring the volcano. NASA’s GOES-17 satellite also played a crucial role in observing the eruption’s effects from geostationary orbit.

Planet Labs operates a satellite network known as PlanetScope, which comprises numerous small satellites, including the Doves and the larger Skysat satellites. The Skysat satellites, equipped with high-resolution imaging capabilities, captured many early eruption images.

ESA's Sentinel 2 satellite offered optical images of the area post-eruption, although its resolution is lower than that of the Skysat satellites. GOES-17 provided GIFs on social media, illustrating the vast ash cloud and shockwave emanating from the eruption.

The second video, Hunga Ha'apai (Tonga) Eruption and Tsunami: The Geology Behind the Headlines, delves into the geological factors contributing to this explosive event and its broader implications.

In addition to these optical satellites, radar satellites, such as ESA’s Sentinel 1, were able to penetrate through the ash and cloud cover to document the initial signs of devastation before optical satellites could resume imaging.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption is now recognized as the largest of this century, following the significant eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991. While such eruptions can lead to temporary drops in global temperatures, the human cost is immeasurable.

To understand the enormity of this eruption, it's essential to consider the geological context. The Pacific Ocean is encircled by the Ring of Fire, where numerous volcanoes are active. In Tonga, the Pacific tectonic plate is subducting beneath the Australian plate, leading to melting rocks and explosive volcanic activity.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai measures over nineteen kilometers in width at its base and contains a caldera approximately five kilometers across. This volcano has exhibited activity since at least 1912 and has shown stability with the emergence of flora and fauna on the island during quieter periods.

Fortunately, as of January 19, aid from New Zealand and Australia began arriving, and communication lines have been partially restored, allowing for the flow of information regarding recovery efforts.

For further insights and updates, consider these resources:

- Tonga volcano: New images reveal scale of damage after tsunami (BBC News)

- Tonga volcano felt around the world (EarthSky)

- The Tonga eruption explained, from tsunami warnings to sonic booms (National Geographic)

- Report on Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai (Tonga) — 12 January-18 January 2022 (Smithsonian Institution)

- Expanding Islands In The South Pacific (Planet Labs)

- Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai Erupts (NASA Earth Observatory)

This article was prepared for the Daily Space podcast/YouTube series. For more news from Dr. Pamela Gay and Erik Madaus, visit DailySpace.org.