Understanding the Risks of Rushed Vaccine Development

Written on

The Covid-19 vaccine has garnered immense anticipation, placing significant pressure on the World Health Organization (WHO) and various medical institutions globally. This urgency can lead to the temptation to expedite processes in hopes of saving lives. However, historical evidence suggests that hastily produced vaccines can result in increased fatalities and potential mutations of the virus, complicating efforts to control it further.

This urgency is exacerbated by the public's disregard for health restrictions, which places additional stress on health organizations when the focus should be on educating citizens about the importance of thorough vaccine development.

In this article, I aim to encourage a more measured approach to vaccine development, emphasizing that while creating a vaccine is a complex task, rushing the process can lead to severe side effects, prolonging the pandemic. I will provide examples from history where expedited vaccine creation led to dire outcomes.

The Polio Vaccine (1955)

Poliomyelitis, or polio, is a devastating illness that targets the nervous system, often leading to paralysis within hours, especially in young children. American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who contracted polio at 39, became a notable figure associated with the disease.

In 1951, as polio cases surged, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis sought a vaccine. They funded Jonas Salk's research at the University of Pittsburgh. By 1953, Salk had promising results using formaldehyde to inactivate the virus while preserving immunity. Confident in his findings, he tested the vaccine on himself and his family.

A widespread trial began with 420,000 children receiving the vaccine, while 200,000 received a placebo. The first recipient was a six-year-old named Randy Kerr. Results indicated that unvaccinated children were three times more likely to become paralyzed.

On April 12, 1955, the US government announced the vaccine's success. However, in the rush to mass-produce, Cutter Laboratories mistakenly released vaccines containing live virus, triggering an epidemic with 200,000 cases in the first month alone. The production was halted, but thousands of children faced paralysis due to the delay in delivering the correct vaccine.

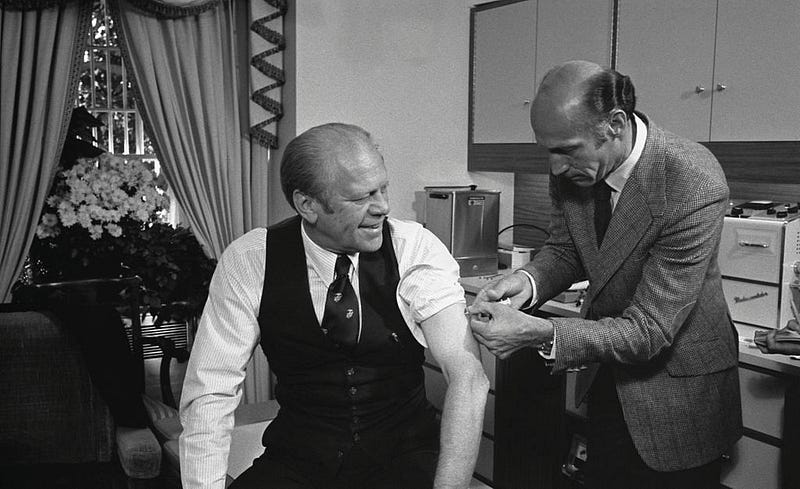

The Swine Flu Vaccine (1976)

In 1976, predictions of a swine flu pandemic prompted urgent vaccine development. Historians later labeled this event a "pandemic that never occurred," as the vaccination campaign caused more harm than good.

Oncologist Michael Kinch warned President Ford of the potential severity of the swine flu, reminiscent of the deadly 1918 Spanish flu. Urged to act quickly, Kinch expedited vaccine development, minimizing necessary testing.

After vaccinating 40 million Americans, numerous recipients developed Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare disorder affecting the nervous system, leading to severe muscle weakness and paralysis. Due to these unexpected side effects, the vaccination campaign was abruptly halted after thousands were affected.

The Rotavirus Vaccine (1998)

In 1998, the FDA approved a rotavirus vaccine, crucial for combating a highly infectious stomach virus affecting infants. Desperate for a quick solution, the vaccine Rotashield was developed rapidly. However, following its administration, instances of invagination—a severe intestinal complication—were noted among infants.

Initially, the correlation between the vaccine and invagination was not recognized. However, as patterns emerged, the CDC halted the vaccine's distribution and production. A new vaccine was later developed after extensive testing.

These cases illustrate the peril of rushing vaccine development, often resulting in inadequate testing and unforeseen complications that arise post-administration. Although not exhaustive, these examples highlight the need for caution in vaccine production.

The Covid-19 vaccine's extended development time reflects this necessity. While there are hopeful signs, the vaccine must be thoroughly refined to ensure its safety for mass distribution. I hope this article prompts reconsideration among those advocating for expedited vaccine development.

Ultimately, would you prefer to endure a few more weeks of waiting, potentially saving countless lives, rather than risk a compromised solution? Learning from history can prevent unnecessary tragedies stemming from hasty decisions.

For further insights on pandemic resolutions, see my previous article on how prior pandemics concluded.

Reference

Between hope and fear: A history of vaccines and Human Immunity by Michael Kinch (2018)