Combating Misinformation: Insights from History and Science

Written on

Visiting Stonehenge is an enchanting experience; its iconic reputation as one of the world's most recognized ancient sites is undeniable. However, the stone circle also exudes a unique mystical charm.

What led ancient people to this site as far back as 10,000 years ago? Archaeologists discovered four large Mesolithic postholes dating back to around 8000 BC, three of which align in an east-west direction, located beneath the current parking lot.

The stone circle we see today was likely constructed around 2500 BC, though the central crescent of bluestones may have been transported from 250 km away and placed in their current formation as early as 3000 BC. This timeline makes it contemporaneous with the first Egyptian pyramid, the step pyramid of Djoser, built around 2620 BC.

Unlike the Egyptians, our understanding of Stonehenge and its builders remains limited, contributing to its allure as a persistent mystery, a puzzle shrouded in the mists of time.

Perhaps this is why, during a sunset visit to the megalith with a local archaeologist years ago, we encountered a diverse group of individuals in robes, engaged in prayer to the stones. Two women bowed fervently before the Sarsen stones, led by a man dressed in flaxen robes.

This phenomenon is unsurprising. The absence of historical context surrounding Stonehenge allows visitors to project their own meanings onto it—prompting the emergence of Celtic revivalists like the Druids and claims that Jesus Christ visited during his ‘lost years’ between the ages of 12 and 30.

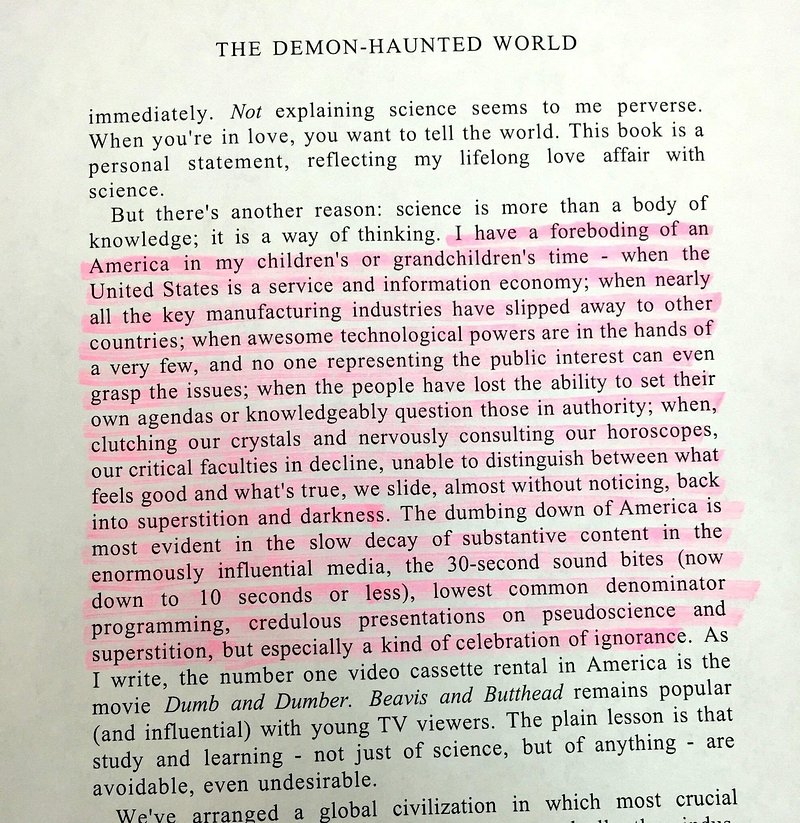

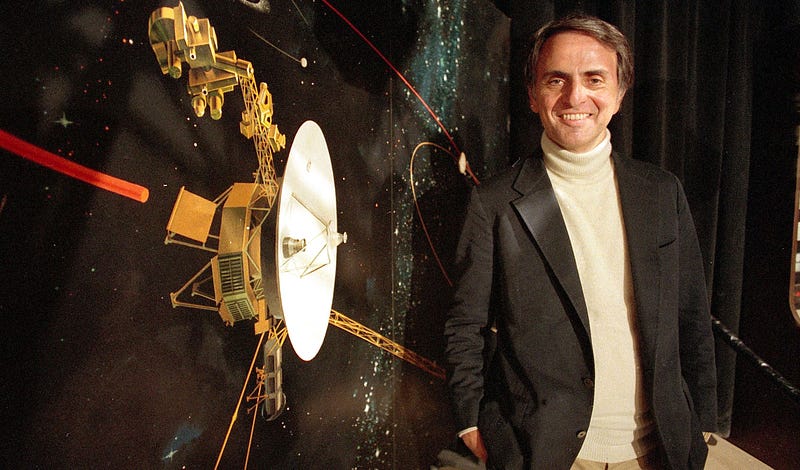

In his insightful work, The Demon-Haunted World, the late astrophysicist Carl Sagan offers a skeptical examination of various superstitions, hoaxes, and pseudosciences. He explores why individuals gravitate towards fantastical explanations for unusual phenomena when credible evidence is lacking and rational alternatives abound.

Sagan recounts the tale of José Alvarez, a 19-year-old American ‘psychic’ who visited Australia in 1988, claiming to channel the spirit of a 2,000-year-old healer named ‘Carlos.’ He asserted that he could communicate with the deceased and cure terminal illnesses. In reality, he was a fictional character created by an Australian television program to showcase human gullibility. Despite being exposed as a fraud, he captivated thousands and attracted enthusiastic crowds at the Sydney Opera House before his deception was revealed.

Sagan noted that this incident demonstrated, “how little it takes to tamper with our beliefs, how readily we are led, how easy it is to fool the public when people are lonely and starved for something to believe in.”

Sagan's foresight concerning today’s world is striking. A passage from the same book has circulated widely on social media in recent times, particularly on Twitter, and its prophetic nature is remarkable:

“I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or my grandchildren’s time—when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are concentrated in the hands of a few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness.”

Indeed, Sagan was astoundingly accurate. As a species, we often succumb to mass delusions, pseudoscience, hoaxes, and the paranormal. Even after a hoax is uncovered, such as the case of ‘Carlos,’ some individuals persist in their original beliefs. The prevalence of conspiracy theories, especially those surrounding COVID-19—ranging from the notion that it doesn’t exist to claims of digital microchips in vaccines—illustrates our tendency to gravitate towards simpler, more comforting, or more sinister narratives regarding the mysterious and unexplained.

So, why do individuals cling to such delusions despite scant and unconvincing evidence? Why do some people assert there’s a ‘face’ on Mars when it has been debunked as an optical illusion, or consider crop circles to be extraterrestrial artifacts despite the explanations provided by the pranksters who created them?

Why do people continue to believe in the existence of a lost advanced civilization known as Atlantis, despite the absence of credible evidence, or in the efficacy of acupuncture, chiropractic, and homeopathy for serious conditions, when numerous reliable studies contradict these claims?

Human perception is notoriously unreliable; differing accounts from witnesses to an event can often yield conflicting narratives. Yet, the allure of conspiracy theories and the supposed prophecies of Nostradamus continue to captivate many.

Collective delusions have occurred throughout history, as sociologists Robert Bartholomew and Erich Goode note, detailing how false or exaggerated beliefs can arise spontaneously and spread rapidly within populations. They provide numerous examples, from the panic over head-hunters in Banda, Indonesia, in March 1937, to the windshield pitting epidemic in Seattle in April 1954, where previously unnoticed damage was attributed to vandals and eventually to atomic bomb testing.

These phenomena, often inaccurately labeled as ‘mass hysteria,’ arise due to various factors, including rumors, extraordinary public anxiety or excitement, shared cultural beliefs, and reinforcement by mass media or authorities.

Charles Mackay, a Scottish journalist, chronicled human susceptibility to suggestion in his 1841 work, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

What Mackay describes is not merely an academic curiosity; modern instances of mass delusion have devastated jobs, companies, and entire economies. The 2008 global financial crisis began with rampant, unsustainable debt that everyone acknowledged was unreasonable, relying on borrowers to repay amounts beyond their means. Was this not a collective delusion?

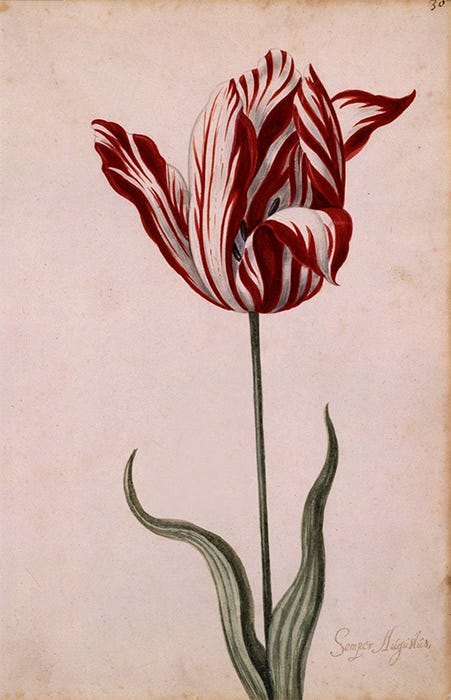

This same delusional behavior reappears during economic cycles of boom and bust. Mackay reminds us of the familiar patterns observed during the ‘tulip mania’ of February 1637, where tulip contracts sold for over ten times a skilled craftsman’s annual income, with one contract even offering five hectares of land for a single Semper Augustus tulip bulb.

From the centuries-long quest to transmute elements into gold to the witch trials in Salem, and from the 17th-century mania for magnets to cure ailments to the extensive military campaigns of the Crusades, collective delusions have been a constant thread throughout history.

These delusions also manifest on an individual level, such as the tales of alien abductions, which bear striking similarities to earlier accounts of demonic encounters. These may be partially explained by sleep paralysis, a phenomenon where individuals are conscious but unable to move or speak while falling asleep or waking up, often leading to hallucinations. Approximately 50% of people experience sleep paralysis at some point, with 5% experiencing multiple episodes.

The human tendency to be bewildered and frightened by the unexplained is unsurprising. “Internally, we are still hunter-gatherers,” says physicist Robert Park, author of Superstition. “The brain that allows us to write poetry and solve complex problems has changed little in 160,000 years. Science has propelled us into an era of advanced technology and communication, yet our brains are still wired for survival in a primitive world.”

Nevertheless, hope exists, particularly within the realm of science. In The Demon-Haunted World, Sagan advocates for the scientific method as a means to overcome fuzzy thinking. He argues that critical and clear thinking enables us to differentiate between profound insights and mere nonsense, asserting that “it is far better to grasp the universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however comforting it may be.”

Sagan proposes a set of critical thinking tools, referred to as the ‘Baloney Detection Kit,’ a nine-step framework designed to help distinguish between fallacies and reality:

- Independent confirmation: Whenever feasible, independent verification of the stated ‘facts’ is essential.

- Debate focused on evidence: Foster substantial discussion on the evidence by knowledgeable advocates of all perspectives.

- Authority is not evidence: Arguments based on authority hold little weight—‘authorities’ have erred in the past and will do so again. In science, there are no authorities, only experts.

- Consider alternative explanations: Generate multiple hypotheses. When faced with an explanation, contemplate various ways it could be interpreted. Then design tests to systematically disprove each alternative. The hypothesis that withstands scrutiny is more likely to be accurate.

- Avoid attachment to a single explanation: Refrain from becoming overly attached to your hypothesis. Compare it fairly with alternatives, and seek reasons to reject it. If you don’t, others will.

- Quantification: If your explanation involves measurable quantities, it becomes easier to differentiate among competing hypotheses. Vague qualitative assessments invite numerous interpretations, while quantifiable data offers clearer insights.

- Consistency: Every link in an argument chain must hold true, including the premise—not just a majority.

- Occam’s Razor: This principle suggests that when two hypotheses explain data equally well, opt for the simpler one, as it is more likely to be correct.

- Testable premises: Always consider whether a hypothesis can be potentially disproven. Assertions that are untestable are not valuable. Propositions must be verifiable, allowing skeptics to follow your reasoning and replicate your experiments.

Sagan’s guidelines help identify common logical fallacies, such as accepting arguments solely based on authority or being misled by small sample statistics. There is no need to be credulous about the extraordinary when reality itself is already fascinating. As Sagan aptly stated, “There are wonders enough out there, without our inventing any.”

Ultimately, Sagan's Baloney Detection Kit encapsulates the essence of the scientific method—a structured approach to critical thinking. As he eloquently expressed, science serves as “a candle in the dark,” illuminating our understanding of the world year by year.

In the end, science is not the answer itself; it is merely the tool that helps us uncover the answers we seek.